Spend enough time with Utah feminists and you'll hear the phrase “the worst state for women” bounce between them on the beat of a metronome. It's their rallying cry, based on a series of less-than-official reports from recent years but firmly reinforced by what the women say they’ve seen around them.

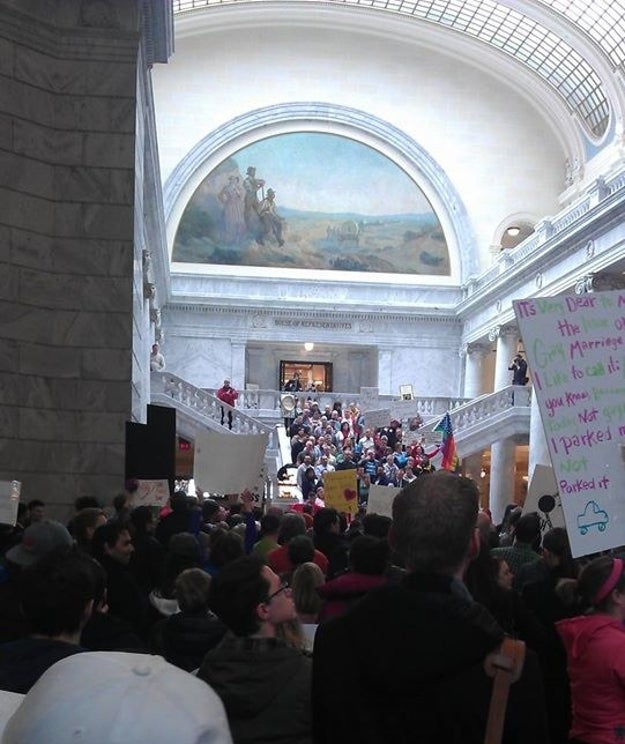

On a snowy night in early January, about 75 of these feminists gathered in Salt Lake City, prepping for the Women's March on Washington on Jan. 21. The venue: a renovated art-deco clubhouse once home to the Ladies Literary Club, a group founded in 1877 by non-Mormon women. The agenda: announcing updates. A location had been picked for the Utah women to gather at before the march began (DC’s National Air and Space Museum), colors for their coordinating outfits had been chosen (black and gold), and final branding had been established (the hashtag #Ifightfor, boxing gloves drawn on posters or worn on hands encouraged).

“The worst state in the nation is here to fight,” said Chelsea Shields, a strategic consultant behind the boxing gloves idea and one of the women coordinating the Utahns' trek to DC. “We want people to say, 'What group is that?' We want our own state to feel self-conscious.”

Kat Kellermeyer wearing her group's signature colors and suggested march accessory: boxing gloves.

Utahwomenunite / Instagram / Via Instagram: @utahwomenunite

The Women's March on Washington started coming together just after the election. It had a chaotic start, well-documented by skeptical media outlets. There was a tangled mess of Facebook pages, then serious concern over whether the march was including women of color and other underrepresented voices (prompting a name change from Million Women March, which had been used by black women in 1997), then questions of permits. By now, though, as DC authorities prepare for a crowd of 400,000, the national organizers have largely whipped the chaos into shape. There are committees and chairwomen and major organizations on board — Amnesty International, the NAACP, Oxfam, Planned Parenthood. The grassroots Facebook effort has gone legit. The national organizers just posed for Vogue. Gloria Steinem is coming.

Still, a narrative of confusion and criticism is hard to stop once it starts, and debate over every aspect of the march continues. On Tuesday, just four days before the march, the event's national organizers were bouncing back from one controversy — granting partnership status to a pro-life group — when another — quietly removing sex worker rights from the march's policy platform — erupted.

But the breathless media coverage of the march has largely overlooked the thousands of women who are simply participating, flying across the country with the daughters, moms, sisters, or best friends they've rallied, or renting a bus for the day — there are more than 1,200 coming to DC — with strangers from their home states. Hundreds have posted to Facebook about how this is their first time demonstrating. Thousands have said they just can't wait for Jan. 21.

The Utah group is stacked with these women, and they’ve got something to prove. Utah went to Trump on Election Day after a brief but convincing flirtation with Evan McMullin, a Utahn who ran for president as an independent. The group of Utah women going to the march is largely white; white women, especially those who supported Trump in red states in secret, are thought to have been the voting bloc that handed Trump his victory. And so the Utahns are going above and beyond many other states' efforts — aggressively planning, branding, coordinating outfits. Organizers say 670 Utah women are going to DC. They started their own organization, Utah Women Unite, to continue advocating for and against state and local policies after Jan. 21. Organizing is in their blood, the Utah women told me.

Kellermeyer and fellow organizer Kathryn Jones-Porter examine pussyhats they'll be bringing to the march in Washington, DC.

Niki Chan Wylie for BuzzFeed News

“We know how to dig in our heels,” said Kat Kellermeyer, a 29-year-old Victoria’s Secret manager. “I feel like that's a uniquely Utahn thing, because so many of us do come from that Mormon background, and Mormons are all about organizing and getting shit done.”

Kellermeyer identifies as “former Mormon,” though she said she hasn't taken her name off the church's official record yet: “I'll see if they're willing to kick me out if I'm active enough in the community.” Kellermeyer is queer, a complicated status in the Mormon faith.

Unlike the handful of longtime activists leading Utah Women Unite, this is Kellermeyer's first time as an organizer. That’s not to say she isn’t aware of activism in Utah; about three years ago, when marriage equality protests and rallies began breaking out, Kellermeyer would go to the capitol and take selfies and post them on social media in support of the demonstrators. This exposure to activism incidentally brought her out of the closet.

“I remember one day, my parents were a little concerned,” she said. Her parents are both “conservative LDS folks” (and proud supporters of Trump, whom Kellermeyer refers to as a “clear and present danger”).

“My father messaged me being like … 'This isn't your fight. What are you doing? You don't have to be so vocal about these issues,'” Kellermeyer said. “I was like, 'It is, though! It is, though.' I just kind of came out. I unloaded.” Kellermeyer now refers to this as her “very millennial way to come out” — over Facebook message.

Since then, her parents have “come a long way, but I wouldn't say we're there yet,” Kellermeyer said. “It's clear they don't always understand me, but I know that they love me. That sounds like the big gay cliche, but it's getting there. It's taking a while.”

A Marriage Equality protest photo that Kellermeyer posted on Instagram.

Kat Kellermeyer

While she told her coming-out story, another one of Utah Women Unite's organizers appeared, wearing a “Wild Feminist” T-shirt and “pussyhat,” a hot pink cat-ear beanie designed for marchers. “It's freezing labia outside,” the woman said.

“It's freezing labia right here, girl!” Kellermeyer replied, pointing to the door cracked open near us. She pulled her hoodie around her fists and rubbed her ears, temporarily obscuring her black gauges stamped with white anchors. Eventually Kellermeyer was summoned to a small breakout meeting of Utah Women Unite organizers, who were practicing what they'll say if the media approaches them at the DC march. One question they anticipate, from Utah media at least, is why supporting LGBT people is part of their group's platform.

“At our first meeting,” veteran organizer Kate Kelly informed the group, “we had a woman come in and say, ‘If you take LGBTQ out of it, I'll support you and I'll bring thousands of women to your march. You have to take that out. You can let Equality Utah fight for them.’”

“Like suffragettes part two,” another marcher remarked, rolling her eyes. “But with gay people.”

“We made that statement so everyone knows where we stand, and we're not taking anyone out,” Kelly said. “Another thing they might ask is, in our mission statement is the word ‘intersectional.’ I've included a definition.”

The women, a group of about 10 — half of whom had never done anything like this, half of whom were seasoned protest pros — went around the circle practicing their personal stories for when reporters ask why they are marching. Some eyes watered. When it was her turn, Kellermeyer talked about her neighbor who calls her a dyke and mutters threats under his breath in passing.

Because LGBT people are not a protected class in Utah, Kellermeyer said, “Until a brick goes through my window and hits me, I can't do anything about it, and even then I can't say it's a hate crime. All I can say is it's destruction of property. There's nothing I can do to protect myself.”

Trump's election made Kellermeyer an organizer. “It's not enough to be woke anymore,” she said. She believes his presidency will “either turn off an entire generation, or get us to go out there and fight.”

The cost for each Utahn to attend the march in DC was around $1,000, depending on when she booked her trip. Utah Women Unite has raised funds for eight people to go, including Kellermeyer, a self-described “low-income girl.” When she heard that a donor had come through for her, she said she sat in her kitchen happy-weeping.

“As a young queer woman from Utah, to go there and represent and speak … to come out and start swinging, and show that you don't have to have a background in organization, you don't have to have a social [work] degree, you don't have to have a law degree. I'm just a blue-collar retail worker.”

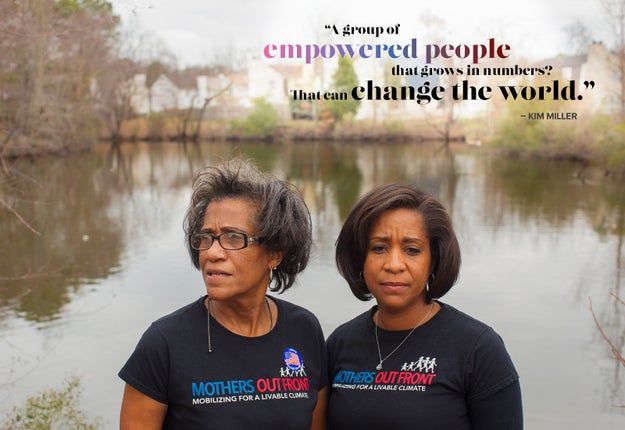

Kim Miller and her mother, Martha Graham, by a pond near their home.

Matt Eich for BuzzFeed News

In 2011, the year Kim Miller turned 40, she decided to do one thing every month that scared her — something she wouldn't ordinarily do, she said. The swamp at Virginia’s First Landing State Park was one of those things.

From the beginning, the park, where she worked as an events and volunteer coordinator, had scared her. First Landing is nearly 3,000 acres — a woodland that passes through a swamp, salt marsh, and sand dunes before emptying out onto a quiet beach. Miller considered herself “suburban,” she said, “used to street lights and controlled environments” and outdoorsy only to the point of playing softball. The park in all its unruly nature was like another planet. And the swamp? “I thought it looked like something out of a scary movie,” she said. The first time she went on a hike in the park's woods, she took a ranger with her, “because he had a gun.”

Her fear didn't stick around long after that; eventually she would walk the trails by herself, or go camping and kayaking in the park. But five years into the job, on the occasion of turning 40, she decided to try one thing in the park she hadn't yet: March out into the swamp.

One step into the swamp, “and I'm going, 'Crap,'” Miller recalled. “I take another step and I'm like, 'This isn't so bad,' and then I take a third step into deeper waters, and there's this hole in my hip waders, so now swamp water is flooding into my hip waders. But it was OK! I survived.”

Miller during her swamp walk at Virginia's First Landing State Park.

Courtesy of Kim Miller

The swamp march has been on her mind as Miller, now 45, prepares for another march. This weekend, she'll load about 55 women onto a bus from Virginia Beach to DC for the Women's March on Washington. Miller and the others will be representing Mothers Out Front, a climate change advocacy group led by — you guessed it — mothers. Miller is bringing her mother, 66, and two of her daughters, ages 18 and 14. (Miller's third daughter, 25, lives in San Diego, “about as far away as she can get without leaving the country,” Miller said, in her most mom-guilt voice.)

Last year, Mothers Out Front, then only based in Massachusetts and New York, expanded to Hampton Roads, the southeastern Virginia region including Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and Chesapeake. At the time, mothers there were particularly concerned about their children being able to get to school during the floods after rainstorms. Hampton Roads, Miller explained, is the second-most-populated area, behind New Orleans, susceptible to flooding. “Throw in high tide and the children are walking in knee-deep water, and that water isn't clean. By the time they get to school they're soaking wet, and a lot of parents are choosing to keep their kids at home.”

To gauge interest in Hampton Roads, Mothers Out Front began holding “something like Tupperware parties, but instead of containers it was climate change,” Miller said. Through her job at the park, Miller had developed a love of conservation that had become entwined with her “love for my children, wanting a livable climate for them and generations to come.” She was also a lifelong Hampton Roads resident, living within walking distance of her parents and other relatives, who'd become increasingly worried about the frequency and strength of hurricanes and other local storms. The Mothers Out Front mission — saving the planet, empowering women — hooked Miller, and she signed on as paid staff.

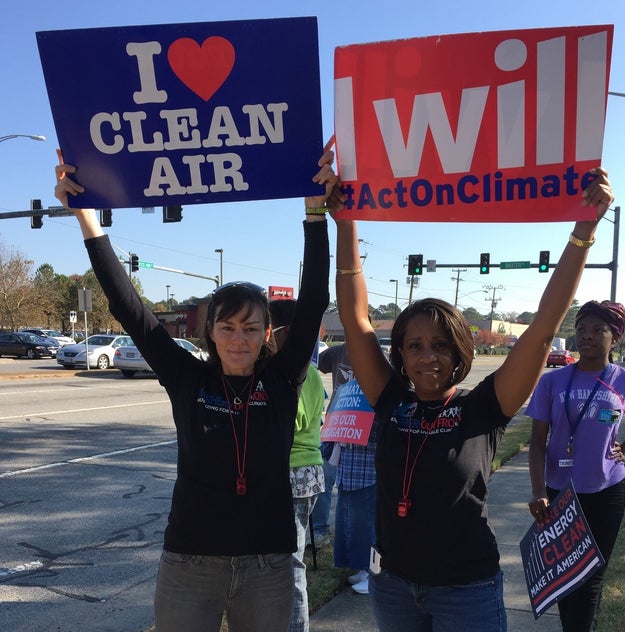

Miller at a Mothers Out Front demonstration.

Courtesy of Kim Miller

“I began to see this is really about investing in our future for our children,” Miller said. “We have to be responsible for that as mothers. That's our job. We worry and we love on them, and we want the best for them, and I really think that's what my children are seeing now: Mommy's doing something.”

“Can tell you a secret?” Miller asked, interrupting her train of thought. “Well, it's not a secret, but can I tell you something?”

In the mid-’90s, before her jobs at Mothers Out Front and the state park, Miller used to be an insurance underwriter. “I used to say no for a living,” she said. “'Your house is old, no. Your kid had a DUI, no.'”

“Hopefully my personality comes across that that would be problematic for someone like me,” Miller continued, laughing. “I felt like it was just a drag on my spirit. To be honest, I didn't like me anymore. I was judgmental, I had a very black-and-white way of thinking. It didn't feel good.”

So she quit. “I didn't leave my family in a lurch” — her husband was making a decent enough amount of money, she said. “It was just important that I did something that fed my spirit as opposed to draining it.”

Even as an underwriter, Miller said, she had conversations about climate change, though from a more corporate standpoint — how to remain solvent if that big storm hits. “I was aware of it but felt helpless to it. It was inevitable, what can you do? And I think as my life and career took these roller-coaster turns, I began to realize one person can't change what's going on, but a group of people — a group of empowered people, a group of empowered people that grows in number? That can change the world.”

Today her work with Mothers Out Front is focused locally, like finding alternate bus routes for schoolchildren in those flooding areas, or guiding what she calls a “merry band of mothers” as they make gas companies plug leaks in their neighborhoods, or trying to persuade Virginia's fossil fuel behemoth Dominion Resources to seriously invest in renewable energy. Mothers Out Front in Hampton Roads has close to 400 email subscribers, Miller said, though the core active membership — mothers who will come to meetings or hold signs at demonstrations — is somewhere in the 20s.

Recently, as Mothers Out Front prepared for the march in DC, Miller got a Facebook message from a young woman who just moved to Hampton Roads, and who was interested in attending the march with a group.

“Her fiancé is in the military and he's deploying on the same day we're leaving for the march,” Miller said. “She just moved in the area and she was really excited, but she's by herself and wouldn't know anyone, so she said, 'Hopefully someone will adopt me.'”

Miller said she responded with “Consider yourself adopted,” sending the woman her phone number and email address.

“Think about the women who have never done anything like this before,” Miller said. “Who gets on a bus with 50-some other women that you don't know to go to DC? I admire her courage, because I don't know how many people could do that.”

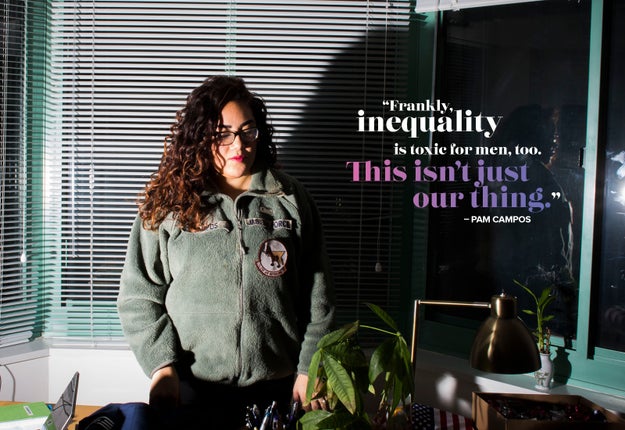

Pam Campos-Palma at her home in Jersey City.

John Taggart for BuzzFeed News

Source: Buzzfeed Before They March: Three Women On Why They’re Going To DC

Add comment