Denise Foreman cringes when she thinks about the doula she used to be.

Like many women, Foreman, 36, became a doula because she wanted to help mothers have empowering birth experiences without being pressured into unnecessary medical interventions. And like many doulas, Foreman was soon strapped for cash, unable to find enough clients who were willing to pay her a living wage — or who even knew what a doula was.

Doulas provide nonmedical physical and emotional support before, during, and right after childbirth with the goal of helping mothers advocate for themselves. The profession isn’t regulated: Unlike nurses and midwives, anyone, even someone who has never been to a birth before, can technically call themselves a doula, which comes from the Greek word for “women’s servant.” There are a few dozen private certification organizations that train professional doulas, and nearly all believe doula care should be accessible to everyone, even if that means working for free or low cost when that’s all an expecting mother can afford.

By 2014, Foreman was a certified doula, but she wasn’t making any money. Her first birth — which she attended for free, because her trainer said she needed the experience — lasted 28 hours. All women deserve doulas, Foreman’s trainer told her, and it was their job to provide. But how was Foreman supposed to provide for her family?

Everything changed when she discovered a private Facebook group called “The Business of Being a Doula,” or “BOBAD.” Most doula websites are decorated with watercolors of earthy women cradling their bellies or flowers that look like vaginas. BOBAD, which has over 10,000 members, features a peppy career woman fist-pumping in front of her computer. The group’s members were unusual, too. They didn’t think every woman deserved a doula. Instead, they considered doula support a luxury — one that ideally came with a premium price tag.

Denise Foreman

Megan Mack for BuzzFeed News

At first, Foreman thought BOBAD was “kind of scary,” she said. Group members accuse volunteer doulas of “devaluing” the profession, calling them selfish “oxytocin vampires” for soaking up secondhand vibes at the expense of their colleagues’ paychecks (women release oxytocin, called the “love hormone,” during labor). “Sure hope that birth high is worth taking the food out of my children's mouths,” an angry doula once wrote about a competitor advertising free services. Posts about whether doulas are a “necessity” draw hundreds of impassioned comments. “Everyone deserves a doula is a catchy phrase,” one doula recently wrote, “but so is ‘show me the money.’”

Foreman stuck around, because, she said, the women “were obviously successful, and I wanted that too.” She soon learned that the group was run by ProDoula, a new, for-profit doula certification agency. The mandate to “charge your worth” was coming straight from ProDoula’s charismatic commander in chief: Randy “Rock N' Roll Doula” Patterson.

Patterson, 49, has breast-length black curls and elaborate tattoo sleeves on both arms. She’s disarmingly effusive, unless she’s talking about the people who’ve crossed her, of whom there are many — her critics compare her to Donald Trump. ProDoula’s attackers need to take a deeper look within, Patterson said in a recent interview at the company’s headquarters in Peekskill, a cute Westchester County town an hour’s drive from New York City.

“If you're not successful, it's because of you,” Patterson said. She wore a leopard-print top and black mesh spike heels as she held court in her purple-walled office, which is decorated with posters of rock bands, goth-chic candelabras, and a mounted unicorn head. A diamond-shaped award Patterson received at ProDoula’s first conference in 2015 sits on her glass desk: “You withstood pressure and remain strong, beautiful, brilliant.” She won it for standing up to ProDoula’s haters.

ProDoula is only three-and-a-half years old, but its co-founders — Patterson and her longtime business partner, Debbie Aglietti — say it’s the fastest-growing doula certification company in the country. It’s also the most controversial. While other leading organizations prioritize the needs of mothers, ProDoula also focuses on the needs of doulas, helping them turn “their passion into a paycheck,” through business-centered trainings and support. Patterson and Aglietti say they’ve earned six-figure incomes working in the doula industry. If they can do it, why can’t you?

ProDoula’s hardline stance has divided the birth world like never before. Doulas have long said they could transform the nationwide birth industry if they could reach more of the nearly 4 million women who give birth each year — just 6% had a doula at their birth, according to one 2013 survey. Whether covered by Medicaid or private insurance, more money is spent on childbirth than any other type of hospital care, and Donald Trump's vow to end Obamacare could make pregnancy even more of a financial nightmare. Decades of research shows doula support reduces the need for major and costly medical interventions such as epidurals, inductions, and cesareans. One 2013 study found that women at risk for adverse birth outcomes were less likely to have complications with a doula by their side, and in 2014, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists acknowledged the doula as “one of the most effective tools” to improve birth.

Randy Patterson's office decor

Megan Mack for BuzzFeed News

For these reasons, doula organizations often encourage their members to volunteer, offer sliding-scale prices, and partner with community-based programs that subsidize doulas for low-income families. Increasingly, some lobby to have doula services covered by Medicaid and private insurance in hopes of a more comprehensive overhaul, cutting costs to patients and creating more steady jobs for doulas — one recent study found professional doula support could save nearly $1,000 a birth. That’s why ProDoula’s insistence that doula services are a luxury, not a necessity, unsettles so many: It clashes with the research the doula movement was built on.

But Patterson has a different perspective on how to make birth better, and it starts with doulas’ bank accounts. “People who have money change things,” she said. She believes targeting higher-income clients will turn the profession mainstream and prevent burnout. Female-dominated care work is historically underpaid and undervalued, and ProDoula wants to fix that by shattering stereotypes that doulas are crunchy home-birth hippies or radical activists who will work for free. Too many women “have a weird time asking for money” and don’t value themselves, Patterson said, which is why ProDoula preaches self-esteem as part of its business model.

“I care more about many of these women than any other fucking person on the planet,” Patterson said. “ProDoula is more than a certification organization. It's everything I have ever stood for as a woman.”

Denise Foreman had to go on a payment plan to afford her first ProDoula training, which at the time cost $1,025 for two days of not only labor and postpartum classes but also, well, reprogramming.

“I was given the freedom to remove the weight of women's birth outcomes from my shoulders,” she later wrote. “I was told that if I want something, I can have it.”

Eventually, with the help of ProDoula’s “Advanced Business Training,” Foreman launched her own doula agency, presiding over a team of ProDoula-trained doulas. Once, Foreman had charged $250 per birth, if she charged anything at all. Now, her agency raked in $1,200 per birth — much more than the local average — plus extra for longer labors and other services. Last year, Foreman moved her family from Issaquah, Washington, to become ProDoula’s executive coordinator of trainings, which is kind of like a cardinal moving to the Vatican to work alongside the pope. Sitting in ProDoula’s HQ, Foreman, who wore double buns in her brown hair and large heart-shaped hoop earrings, cried as she described her transformation. Patterson was right beside her, instructing her firmly but lovingly to “hold it together.”

Patterson (right) working with a client.

Raymond Forbes

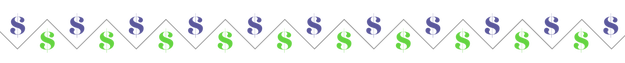

Thanks to women like Foreman, ProDoula says it made $1.25 million in 2016. The company has nine full-time employees, 15 paid trainers, and an array of pricey services available for purchase, from placenta encapsulation kits to one-on-one coaching packages. The company says it has processed more than 3,000 certifications across the US, Canada, and Europe since it started, with triple-digit growth percentages in its first two years and nearly 50% in 2016. Patterson and Aglietti co-own three doula agencies across the country and plan on opening two more in 2017.

Despite ProDoula’s success, many of its members say they feel like outsiders in their local doula communities. When Foreman made the crossover, other doulas called her “money-hungry,” she said. Her blog posts from that time sound like they were written by a political radical. “There is a #doularevolution happening. And I'm part of it,” she wrote. “Doulas are succeeding and the ones who balk, badmouth and shame are going to be left trapped in the subterranean bitumen, burned out and broke.”

But where ProDoulas see community, critics see a cultish crew of snake-oil salespeople. Patterson was once a star Mary Kay consultant, and she’s applied some of the cosmetic company’s marketing practices to ProDoula, leading to questions about whether its success benefits all women, or just those at the top.

“The doula movement was founded on the needs of the woman,” said Penny Simkin, the beloved 78-year-old co-founder of DONA International, which bills itself as the world’s oldest, largest, and most respected doula-certifying organization. ProDoula’s business strategy “will do nothing for improving birth in this country,” she said, “and only improve their pocketbooks.”

Women have been “doula-ing” for centuries, but it only became a profession in the 1980s, after hospitals’ cesarean and medical induction rates spiked. Amid growing concerns about the country’s unreasonably high maternal and fetal mortality rates, research found that continuous emotional, patient-centered support during labor resulted in better maternal and infant health. The most effective support, studies show, comes from specialists who aren’t family members, friends, or hospital employees. Enter the doula.

At first, medical professionals saw doulas as activist interlopers. But in 1992, a group of doctors and maternal health experts launched the nonprofit now called DONA International. DONA’s stated vision was and is “a doula for every woman who wants one,” but it also aimed to professionalize the industry with trainings and a code of conduct for doulas.

Doulas who train through DONA meet with pregnant women to create a birth plan, regardless of whether the client wants an “all-natural” delivery or a speedy epidural. During labor, the doula acts as a negotiator, helping to make sure the plan is followed without stepping on the medical team’s toes if complications arise. They check in after the birth to make sure everything’s going okay (there are also postpartum doulas who focus solely on post-birth care).

Thanks in part to our on-demand economy, doulas are now more popular than ever. But although 2016 may have been “the year of the doula,” it’s also a time of crisis for the unregulated industry. There are conflicts between those who believe doulas should support their clients autonomously, and those who want doulas to collaborate with the medical system. There are doulas who want to be subsidized by Medicaid defending their reputations against “renegade outlaw” doulas who oversee illegal home births. There’s tension between self-declared radical doulas who serve marginalized communities and trendy “celebrity doulas” who cater to the “wellness”-obsessed elite. (“You know what a doula is? A white hippie witch that blows quinoa into your pussy,” comedian Ali Wong recently quipped on her Netflix special.)

There is one thing most doulas do have in common: They don’t make much money.

A doula lucky enough to sign three labor contracts a month at $800 each — the average national fee for an experienced, certified labor doula, according to one analysis — won’t even net $30,000 a year, without accounting for expenses like training fees, advertising, and child care.

“I care more about many of these women than any other fucking person on the planet.”

Yet most doula certification organizations shrug off the business side. Melissa Harley, DONA’s PR director, said one survey found only half the doulas who train with them plan on being full-time professionals, which is why they have some “business-themed offerings” but don’t focus on finances. “We believe that doulas can be empowered to make their decisions for their own individual practices,” she said.

But ProDoulas claim that trainers at DONA and other organizations often dissuade and even shame those who want to make a living.

“When expectation is set that doulas will do free or low-cost births, then people expect to get a doula for free or low cost,” said Catie Mehl, a ProDoula trainer in Ohio. When she loses a client to someone who charges less, “I’m like, I can’t feed my family now today,” Mehl said. “That’s personal.”

Mehl used to be a DONA trainer, but wasn't making enough money to pay the bills, she said. She nearly quit doula-ing completely. Instead, she joined ProDoula.

It’s difficult to find a ProDoula who hasn’t been personally inspired by Patterson.

“She just turned this bright light on me,” said Leanne Palmerston, a ProDoula trainer in Hamilton, Ontario.

Randy Patterson with ProDoula partner Debbie Aglietti

Megan Mack for BuzzFeed News

Patterson “knows exactly how to raise someone up and give them the inspiration to do amazing, huge things,” Palmerston said. “My dreams before were real small, like, I’d like to make enough money that maybe there’s an extra $1,000 in my budget every month, and she was like, ‘Lady, you can go buy yourself a house, a car, create a retirement for yourself, start multiple agencies. You can dream the whole world and hire other people to do the work for you.’ I was like, ‘Holy shit, I didn’t know I could dream that big.’ That’s what Randy gives us.”

Even Patterson’s life story is made-for-TV inspirational. Patterson’s parents were artsy junkies in Monroe, New York, who loved her but left her “a fucked-up kid with no self-esteem.” A high school dropout who was briefly homeless, Patterson claims she had no aspirations beyond being a good wife and mother to her two daughters.

Then, a mother at Patterson’s kids’ school helped her get an assistant job at her local hospital’s birth center. Patterson had no medical experience, but she was a natural who loved helping women in labor feel confident. It was an easy transition to independent doula work. Patterson ran her own business before partnering with Debbie Aglietti to start an agency called Northeast Doulas (Patterson calls Aglietti the “Greenwich, Connecticut” to her “Greenwich Village” because Aglietti prefers tasteful pearls to leopard print.)

The Radiant Project / YouTube / Via youtube.com

Source: Buzzfeed

Add comment